Smarter Asserts

Discusses a problem in Unreal's error handling and solves it by creating custom asserts that crash only the PIE session.

Summary

Error handling is very important in computer programming. It is how most programmers avoid bugs and glitches. There are many different types of errors, both minor and major, and so there are different types of error handling. I noticed Unreal Engine had a significant blind spot in error handling, and have created a fix for it.

Definition of Error

If you have read to this point, you probably don’t need the dictionary explanation of an error. Instead, I will specify what types of errors this article is about. Unreal is written in C++, and although the source code is able to be modified and recompiled, this article does not consider error handling in the language or Unreal itself. (Thread-safe, memory leaks, hardware restrictions)

This article only considers errors created by the programmers working on a game made in Unreal. Both custom C++ code and Blueprint scripts can have errors. Null pointer errors are the most common, but other runtime errors can also apply. There are some logic errors which can have Error handling, but only those that can be foreseen. A good example of this is sequence-breaking the game. If a player goes into an area they shouldn’t be in, it wouldn’t be that difficult for a programmer to add a check to move the player to an appropriate position. A bad example would be the player getting stuck in geometry, since making a check to see if the player is stuck would require editing Unreal’s source code.

Existing Error Handling

Unreal has quite a few options for error handling.

1. Exception Handling

If you’re familiar with C++, you might know what this is. While Unreal is built in C++, it does not support exceptions. It may be possible in very specific use cases, but it is better to not upset Unreal (it’s an angry master). Instead, return a bool or enum that represents the error and pass the output by reference in the parameters.

1

2

3

4

5

6

bool bIsInitialized;

// Returns true if there is no error

// @param result The object activated in the pool.

UFUNCTION(BlueprintCallable)

bool UObjectPool::Request(UPoolableObject*& result);

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

bool UObjectPool::Request(UPoolableObject*& result)

{

if(!bIsInitialized)

return false;

//Do something and set result

return true

}

Functions created in Blueprint are also able to have multiple outputs.

This is good for core or backend mechanics. In this example, a weapon can execute custom logic when it fails to fire a projectile from the pool. This is more explicit than the object pool returning a nullptr.

This can make APIs cluttered. Also, it can be disruptive to C++ programmers who have to use the out parameter as the real returned value.

2. Print to Log

Displays an error message of some sort. In Unreal, there are two main destinations for output, the log and the on-screen debug messages. unfortunately, not every developer looks in the output log, and the on-screen message can be missed if it times out or gets pushed offscreen by newer messages.

1

2

3

4

5

bool bIsInitialized;

// Returns the object activated in the pool.

UFUNCTION(BlueprintCallable)

UPoolableObject* UObjectPool::Request();

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

UPoolableObject* UObjectPool::Request()

{

if(!bIsInitialized)

{

// Print to log

UE_LOG(LogTemp, Error, TEXT("Object pools need to be initialized before an object can be requested from it."));

// Print to screen

if (GEngine)

{

GEngine->AddOnScreenDebugMessage(-1, 5.f, FColor::Red, TEXT("Object pools need to be initialized before an object can be requested from it."));

}

return nullptr;

}

}

The Blueprint function Print String or Print Text can output to the screen and log.

This is good for minor or non-fatal errors. Idealy, a programmer would notice the error, find why the error occurred, and then fix the bug.

Programmers might not notice the error, or purposefully ignore it thinking it doesn’t have any impact on what they are currently testing. Unlike Unity, errors logged will NOT pause the game.

3. Asserts

Completely crash the engine and bring up the crash reporter. Unreal has several macros that help the engine correctly crash. This is C++ only, and is Unreal’s suggested method of handling errors in C++. If you are debugging from Visual Studio, Rider, or other IDE, it will create a breakpoint instead of completely crashing the game.

1

2

3

4

5

bool bIsInitialized;

// Returns the object activated in the pool.

UFUNCTION(BlueprintCallable)

UPoolableObject* UObjectPool::Request();

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

UPoolableObject* UObjectPool::Request()

{

checkf(bIsInitialized, TEXT("Object pools need to be initialized before an object can be requested from it."))

//Do something and set result

return true

}

Unreal does not have any Blueprint nodes that assert.

This form of error handling is only good when everyone testing the game has a debugger attached (such as running Unreal from Visual Studio, Rider, or another IDE). If a Blueprint-only programmer or designer opened the .uproject directly, an assert will completely crash the editor.

Problem

When I was creating an object pooling system, I set it up so the Initialize or InitializeAsync functions would need to be called on the object pool before it can be used. At the time, I was the only C++ programmer on the team. The designers or Blueprint programmers would be the ones who would use my system to create a weapon system, enemy drop system, and any other system that would benefit from object pooling.

I had to find the best way to handle the error of what would happen if they tried to use the object pool without initializing it. Naturally, they should know to Initialize it first because of the documentation, but everyone makes mistakes in game dev. Even me, and I’m the one that programmed the object pooling system!

If I used the Exception Handling method, then it would be up to the other team members to handle what would happen if an error occured. This is very easy to ignore, though. (Which they most likely would do if they didn’t look at the documentation to call Initialize first.)

If I used the Print to Log method, I would have to print to the screen. The other team members don’t look in the log often, and if they would, it would most likely be flooded with other Unreal messages, making my error message less visible. Printing to the screen is more visible, but still not as obvious as it could be. Also, the code for printing to the screen is big and clunky.

If I used Asserts, then the other team members would be very annoyed. They don’t normally run Unreal with a debugger, so they would have to restart the entire editor after it crashes. While this would successfully notify them of the error they made, it is a little too extreme.

Solution

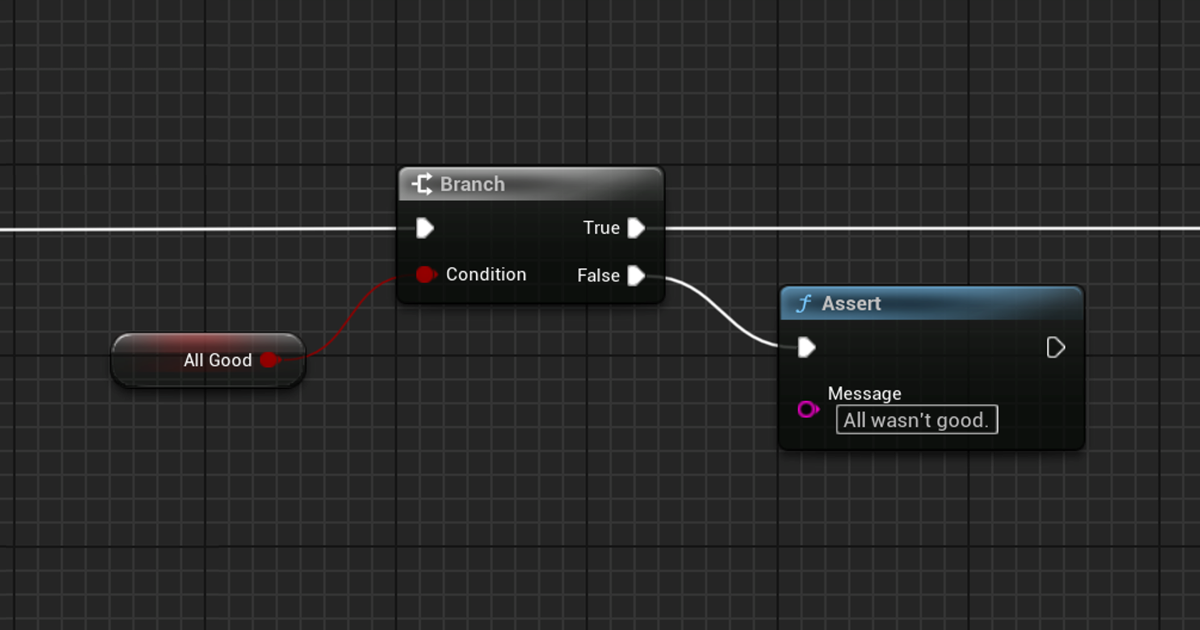

There should be a way to crash the game, known as Play-In-Editor (PIE), without crashing the entire editor. Unreal doesn’t have any natural way of this happening. In my research, I noticed pieces of an unimplemented system that is supposed to pause the game whenever an error happens in Blueprint. This inspired me, so I worked on creating my own way to crash just the PIE session. I called this Smart Asserts.

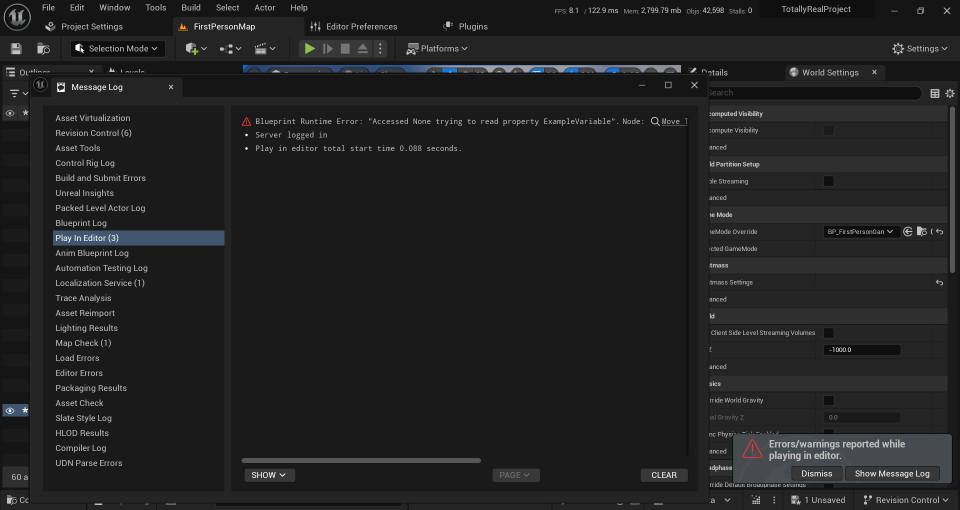

There is a second form of output that Unreal can print to other than the Output Log. This is the Message Log. When an error is sent to this output, it will pop up automatically when the PIE session ends. This normally happens with

There is a second form of output that Unreal can print to other than the Output Log. This is the Message Log. When an error is sent to this output, it will pop up automatically when the PIE session ends. This normally happens with Blueprint Runtime Errors, such as when a function is called on a nullptr. With those errors, Unreal is smart enough to ignore the function call, preventing any actual errors that would crash the game.

However, I want the game to crash. I created a macro, scheck, meaning safe check, that would output a message to the log and then call the function UKismetSystemLibrary::QuitGame. This makes the game “crash” at the end of the current frame. With this, when scheck was called it would exit the game and open up the message log, making it obvious there was an error. unfortunately, all the code in the frame would still execute, so any code that relied on the function that threw the scheck would still execute. There is no way to completely stop this from happening.

There is a way to mitigate the amount of code that executes, though. Unreal has a feature that isn’t as used as often as it should. Just like in C++, C#, and other languages, Blueprints can have breakpoints. Calling the function FKismetDebugUtilities::RequestSingleStepIn forces the editor into debug mode and prevents the execution of blueprints after the one that threw the scheck. Oddly, if QuitGame is called right after RequestSingleStepIn, then the game will exit out of PIE even though it went into debug mode. All C++ code would still execute, unfortunately. This makes it best for scheck to be placed as close to the BlueprintCallable function as possible. The scheck macro returns so no code in its scope will execute.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Log the message to the more designer-friendly logger.

FMessageLog PIELogger = FMessageLog(FName("PIE"));

PIELogger.Error(FText::FromString(TEXT("This is an example error message")));

// Stop execution of the blueprint, making it "crash" in the middle of a frame.

// Normally this would put the game into debug mode

FKismetDebugUtilities::RequestSingleStepIn();

// Quit the game. This works even when the editor gets paused, so the user won't notice it went into debug mode.

UKismetSystemLibrary::QuitGame(GEngine->GameViewport->GetWorld(), nullptr, EQuitPreference::Quit, false); //Stop execution of the game

// Stop the execution of C++ code in this current function.

return;

scheck is not intended for C++ only code. Before scheck smartly asserts the PIE session, it makes several checks to ensure it is a PIE session and not standalone, the editor exists, and the C++ code’s execution started from Blueprint. If any of these checks fail, then it will assert regularly, crashing the application. Fortunately, this is expected, since the programmer is either working in C++ and the debugger will catch the assertion or it is a build of the game so it should crash completely.

How to Install

You can find the source code on GitHub, along with the documentation in the readme. It is also published onto the Epic Marketplace (now Fab) as a plugin. The Epic launcher can install the plugin to Unreal automatically.